Two dramatic events in 1990 changed my mother’s destiny and as it turned out, the lives of countless young women and their families around New Zealand. At the time, she was the Deputy Principal of the largest Polynesian secondary school in the world, in one of poorest socio-economic areas of the country.

The first event occurred early that year when she walked into a school bathroom and witnessed one of her students, 15 years old, giving birth on the floor. The second was more statistical in nature: she noticed that the number of young girls attending her school was dropping and no one could understand why. She discovered it was because, just like the girl in the bathroom, students between 12 and 16 were getting pregnant and leaving school never to return.

That’s when she made her first decision: to make sure these girls were given an education regardless of their new status as teenage parents. Indeed, the law in New Zealand specifically states that every child is entitled to a free basic formal education until the year of their 19th birthday. However, when she approached the Ministry of Education to ask about their policy regarding teenage mothers dropping out, she was told there was “no problem so no policy”, and she would be better advised concentrating on her duties as Deputy Principal. In other words, ‘Get Lost’!

You don’t give an answer like that to my mother or women like her. It just acts as “jet fuel” to focus the mind and get on with finding a solution when others won’t.

No one in New Zealand could or would help her as there ‘wasn’t a problem’ so her second decision was to apply for 3 overseas fellowships. She was a dab hand at filling in forms and won two of them. One was to the University of London for an academic year and the other, a concurrent Eisenhower fellowship allowing her to travel to the United States and find out how they were dealing with the education of teenage mothers, where the challenge had been recognised and acted upon.

In London, she studied government programmes and policies, and then went to the US to visit 56 schools in 12 States in 3 months, leaving my brother and I to pretty much fend for ourselves. She met policy makers, school superintendents, researchers, teachers and teenage mothers themselves and listened to their stories to learn what worked and what didn’t towards ensuring they received an education that met their needs. After a year away she couldn’t wait to open her own school knowing it would work.

Armed with the key learnings from the UK and the US, she returned to New Zealand and approached the government again – with a plan this time – and incredibly got the same answer: “Get Lost”!

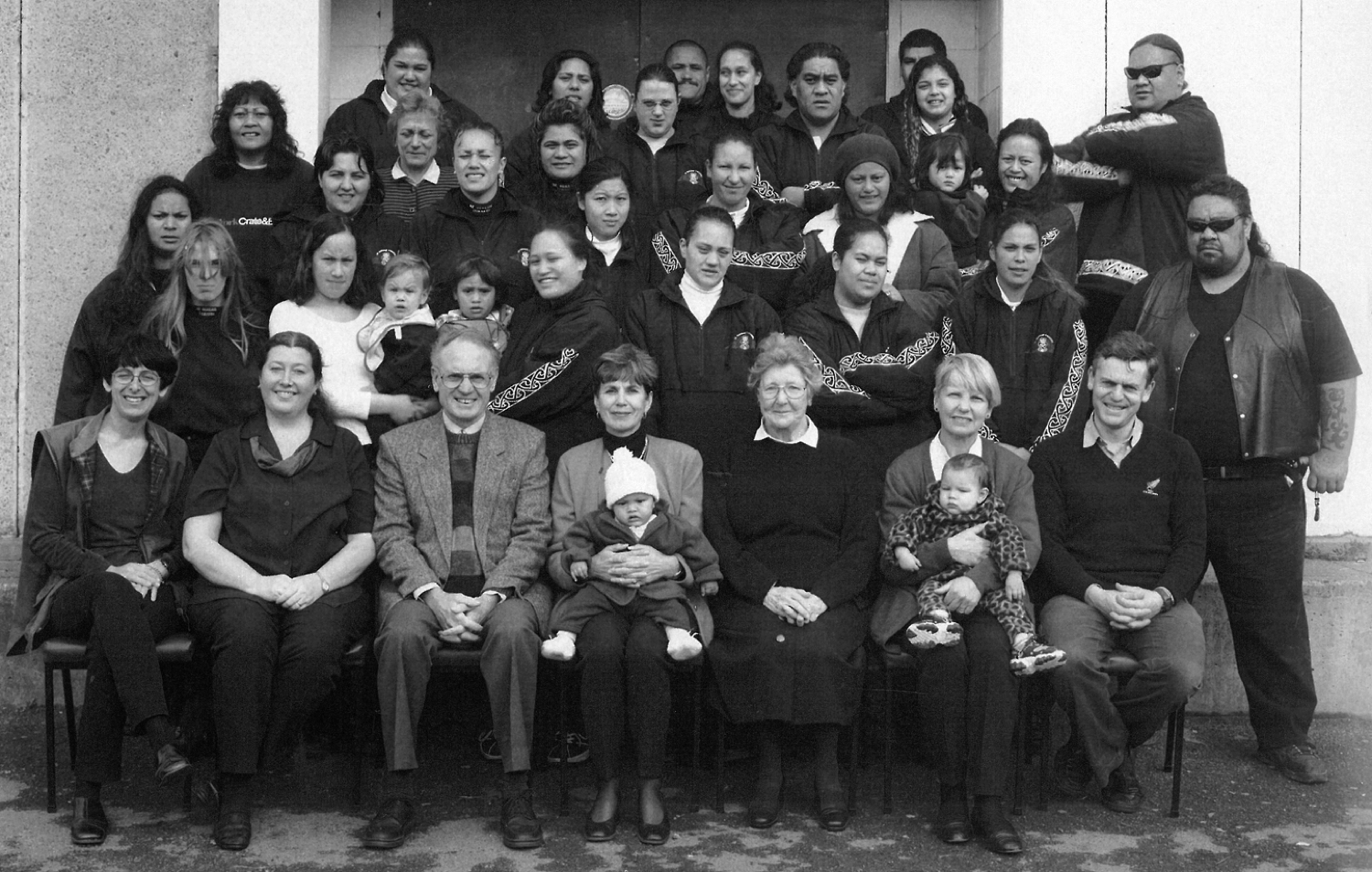

So she made her third major decision: to take matters into her own hands. With no budget, no government support, and armed only with her drive to do the right thing by these girls (and a supportive Principal of her College), she found an abandoned tavern in the local community and converted it into a ‘school inside a school’ with questionable legality. She called up retired teachers persuading them to “un-retire” and found expert volunteers. She went door-to-door convincing young mothers to come to her school, sometimes standing in the chilly unemployment queues, offering them and their babies a free lunch. She spoke at service clubs around the country raising funds in often very uncomfortable conditions, and begged her family and wealthy friends for donations. It worked! The school soon filled to capacity, and to her surprise, young fathers appeared wanting to support the mother and child. These young mothers re-started their education in an environment that met their needs. Each student would take turns caring for the babies while the others studied with the attentive help of experienced volunteers. She found funding for a school bus and hired an ex-gang member as the driver who later went on to become a lead trainer of Wellington City bus drivers. Eventually she obtained a private grant to build a licensed attached childcare facility and after 10 years, the State built a beautiful stand-alone school which the students designed themselves.

She called the school, “He Huahari Tamariki”, a “chance for children” in the Maori language.

Today, there are over 30 schools built on this model around the country with more in the pipeline. The statistics, when they were finally collected, revealed there were 27’000 teenage mothers in New Zealand at the time the school started. There is now a government policy and budget of tens of millions of dollars and the schools have been fully integrated into the education system, meeting the needs of the children the system is meant to serve. Just imagine the human and social capital involved!

Here is what some of the very first students of He Huarihi Tamariki are doing now:

- Helen received her PhD in Chemistry in 2017 having discovered 6 new anti-malarial compounds.

- Marianne is Chief Social Worker for her region and has a Master’s degree.

- Lania is Head of Administration of the attached childcare at the He Huarahi Tamariki school.

- Charmaine became a legal executive and worked in the New Zealand parliament.

- Silvia graduated Bachelor of Nursing and is Head Nurse in a private hospital.

- Ricky (who was 15 when he and Marjory, 14, had their first child) became an electrical engineer and has his own business. Their 2 daughters are now at university, one in her 5th year at medical school and the other studying Science.

The Honours Board seen at the entrance of the school shows qualifications as diverse as Agriculture, Law, Education, Medical Science, Philosophy and Automotive Engineering. Those without degrees have gone on to jobs with good prospects.

Look at what happens when you choose not to leave people on the side of the road or on the couch receiving welfare.

Look at what happens when you give a “hand up” rather than a “hand out”.

Look at what happens when you develop potential in young mothers who want a better life for themselves and their children.

And look at what happens when you take a series of decisions, without knowing the outcome, without necessarily having the tools to succeed, but with the drive and the courage to do what is right, to do what you believe in.

You end up helping to CREATE destinies for those you seek to serve and for yourself.

I consider my mother to be a leader – a kind of “Erin Brockovich of education” – not because of any title or social status. Indeed, she certainly didn’t set out to be one, preferring anonymity and a quiet private life. She became a leader because she saw a problem, was told

that it wasn’t hers to solve, yet proceeded to dedicate her life to solving it anyway, not for herself but, in the end, for all of us to see. That, for me, is the highest form of leadership: where you make decisions that primarily serve others, helping them grow, spread their wings and change the world. It’s like a pebble being dropped in a pond, that creates a ripple that makes a wave that moves an ocean. One decision that you make, followed by another, by another, can change the world for the better. In her Eisenhower application she wrote, ‘I slipped on a stone and caused an avalanche’.

I’d like to end with another quote from Mum …

“People began by asking me “why I was doing this”. Then I was told that I “couldn’t do it”. Even friends said I “shouldn’t do it”… but do you know what the motto of He Huarahi Tamariki is? ‘Of course, you can do it!’.”

She certainly did. They all did!